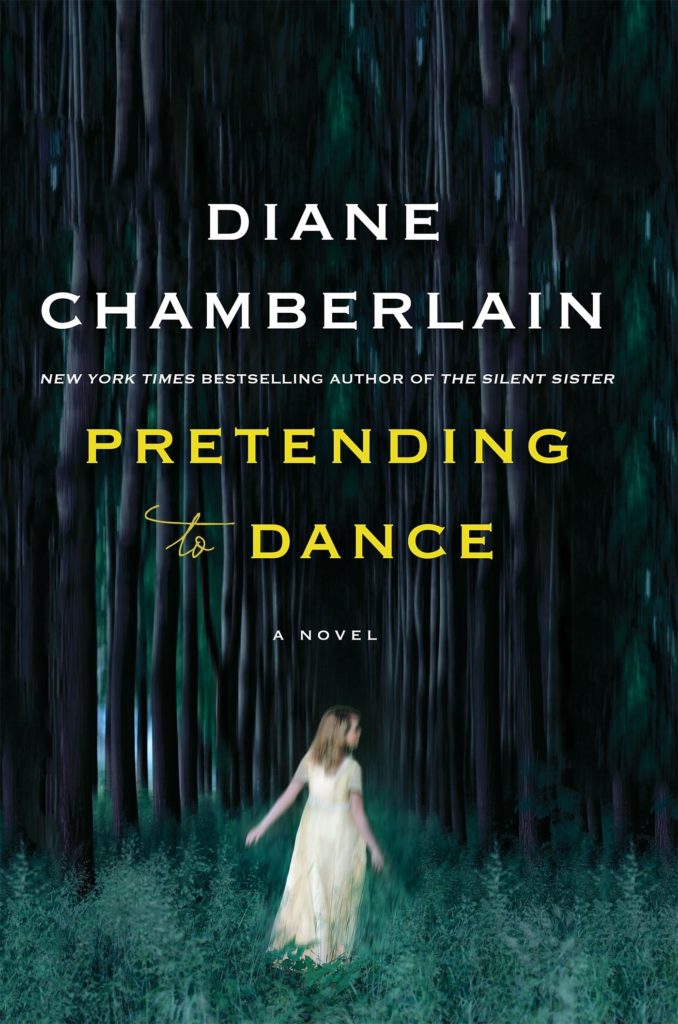

Pretending to Dance

Buy the Book:

Buy the Book:Amazon

Barnes & Noble

IndieBound

Books-A-Million

iBooks

Google Play

Amazon Audio CD

Audible

Published by: St. Martin's Press

Release Date: October 6, 2015

Pages: 352

ISBN13: 978-1250010742

Synopsis

Molly Arnette is good at keeping secrets. As she and her husband try to adopt a baby, she worries that the truth she's kept hidden about her North Carolina childhood will rise to the surface and destroy not only her chance at adoption, but her marriage as well. Molly ran away from her family twenty years ago after a shocking event left her devastated and distrustful of those she loved. Now, as she tries to find a way to make peace with her past and embrace a healthy future, she discovers that even she doesn't know the truth of what happened in her family of pretenders.

Praise

“Exploring the thrilling feelings of first love, the depths of teenage angst, and the difficult decisions families and spouses make together, Pretending to Dance is a multilayered, poignant novel. Chamberlain writes knowledgeably about seeing a family member confront a degenerative illness, the power of therapy, and the hardship of loss. Reminiscent of a Sarah Dessen or Sharon Creech novel, Pretending to Dance proves that a coming-of-age story can happen at any time in your life.”

—Booklist

“While the family argues and Molly's hormones run wild, something else is going on that will make for the explosive revelation at novel’s end.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“A gripping story of a girl’s relationship with her father and how, as a child, we only see what we want to.”

—Woman & Home

Audio Sample

Excerpt

San Diego

2014

1

I'm a good liar.

I take comfort in that fact as Aidan and I sit next to each other on our leather sectional, so close together that our thighs touch. I wonder if that's too close. Patti, the social worker sitting on the other wing of our sectional, writes something in her notes and with every scribble of her pen, I worry her words will cost us our baby. I imagine she's writing The couple appears to be codependent to an unhealthy degree. As if picking up on my nervousness, Aidan takes my hand, squeezing it against his warm palm. How can he be so calm?

"You're both thirty-eight, is that right?" Patti asks.

We nod in unison.

Patti isn't at all what I expected. In my mind I've dubbed her 'Perky Patti'. I'd expected someone dour, older, judgmental. She's a licensed social worker, but she can't be any older than twenty-five. Her blond hair is in a ponytail, her blue eyes are huge and her eyelashes look like something out of an advertisement in Vogue. She has a quick smile and bubbly enthusiasm. Yet, still, Perky Patti holds our future in her hands and despite her youth and bubbly charm, she intimidates me.

Patti looks up from her notes. "How did you meet?" she asks.

"At a law conference," I say. "2003."

"It was love at first sight for me," Aidan says. I know he means it. He's told me often enough. It was your freckles, he'd say, touching his finger to the bridge of my nose. Right now, I feel the warmth of his gaze on me.

"We hit it off right away." I smile at Aidan, remembering the first time I saw him. The workshop was on immigration law, which would later become Aidan's specialization. He'd come in late, backpack slung over one shoulder, bicycle helmet dangling from his hand, blond hair jutting up in all directions. His gray t-shirt was damp with sweat and he was out of breath. Our workshop leader, a humorless woman with a stiff looking black bob, glared at him but he gave her that endearing smile of his, his big brown eyes apologetic behind his glasses. His smile said, I know I'm late and I'm sorry, but I'll make you happy that I'm in your workshop. I watched her melt, her features softening as she nodded toward an empty chair in the center of the room. I'd been a wounded soul back then. I'd sworn off men a couple of years earlier after a soul-searing broken engagement to my long-time boyfriend Jordan, but I knew in that moment that I wanted to get to know this particular man, Aidan James, and I introduced myself to him during the break. I was smitten. Aidan was playful, sexy and brainy, an irresistible combination. Eleven years later, I still can't resist him.

"You're in immigration law, is that right?" Patti looks at Aidan.

"Yes. I'm teaching at the University of San Diego right now."

"And you're family law?" She looks at me and I nod.

"How long did you date before you got married?" she asks.

"About a year," Aidan says. It had only been eight months, but I knew he thought a year sounded better.

"Did you try to have children right away?"

"No," I say. "We wanted to focus on our careers first. We never realized we'd have a problem when we finally started trying."

"And why are you unable to have children of your own?"

"Well, initially it was just that we couldn't get pregnant," Aidan says. "We tried for two years before going to a specialist."

I remember those years all too well. I'd cry every time I'd get my period. Every single time.

"When I finally did get pregnant," I say, "I lost the baby at twenty weeks and had to have a hysterectomy." The words sound dry as they leave my mouth, no hint of the agony behind them. Our lost daughter, Sara. Our lost dreams.

"I'm sorry," Patti says.

"It was a nightmare," Aidan adds.

"How did you cope?"

"We talked a lot," I say. Aidan still holds my hand, and I tighten my grip on him. "We talked with a counselor a few times, too, but mostly to each other."

"That's the way we always cope," Aidan says. "We don't keep things bottled up around here, and we're good listeners. It's easy when you love each other."

I think he's laying it on a little thick, but I know he believes he's telling the truth. We congratulate ourselves often for the way we communicate in our marriage and usually, we do a good job of it. Right now, though, with my lies between us, I squirm at his words.

"Do you have some anger over losing your baby?" Patti directs her question to me.

I think back to a year ago. The emergency surgery. The end of any chance to have another child. I don't remember anger. "I think I was too devastated to be angry," I say.

"We regrouped," Aidan says. "When we were finally able to think straight, we knew we still wanted . . . still want. . . a family, and we began researching open adoption." He makes it sound like the decision to pursue adoption was easy. I guess for him it was.

"Why open adoption?" Patti asks.

"Because we don't want any secrets from our child," I say with a little too much force, but I feel passionately about this. I know all about secrets and the damage they do to a child. "We don't want him--or her--to wonder about his birth parents or why he was placed for adoption." I sound so strong and firm. Inside, my stomach turns itself into a knot. Aidan and I are not in total agreement over what our open adoption will look like.

"Are you willing to give the birth parents updates on your child? Share pictures? Perhaps even allow your child to have a relationship with them, if that's what the birth parents would like?"

"Absolutely," Aidan says and I nod. Now is not the time to talk about my reservations. Although I already feel love for the nameless, faceless people who would entrust their child to us, I'm not sure to what degree I want them in our lives.

Patti shifts on the sectional and gives a little tug on her ponytail. "How would you describe your lifestyle?" she asks in a sudden change of topic, and I have to give my head a shake to clear it of the image of those selfless birth parents. "How will a child fit into your lives?" she adds.

"Well, right now we're both working full time," Aidan says, "but Molly can easily go to half time."

"And I can take six weeks off if we get a baby."

"When." Aidan squeezes my hand. "Be an optimist."

I smile at him. To be honest, I wouldn't mind quitting my job altogether. I'm tired of divorce after divorce and divorce. The longer I practice law, the more I dislike it. But that is for another conversation.

"We're pretty active," I tell Patti. "We hike and camp and bike. We spend a lot of time at the beach in the summer. We both surf."

"It'd be fun to share all that with a kid," Aidan says. I imagine I feel excitement in his hand where it presses against mine.

Patti turns a page in her notebook. "Tell me about your families," she says. "How were you raised? How do they feel about your decision to adopt?"

Here is where this interview falls apart, I think. Here is where my lies begin. I'm relieved when Aidan goes first.

"My family's totally on board," he says. "I grew up right here in San Diego. Dad is also a lawyer."

"Lawyers coming out of the woodwork around here." Patti smiles.

"Well, Mom is a retired teacher and my sister Laurie is a chef," Aidan says. "They're already buying things for the baby." His family sounds perfect. They are perfect. I love them—his brilliant father, his gentle mother, his creative, nurturing sister and her little twin boys. Over the years, they've become my family, too.

"How would you describe your parents' parenting style?" Patti asks Aidan.

"Laid back," Aidan says, and even his body seems to relax as the words leave his mouth. "They provided good values and then encouraged Laurie and me to make our own decisions. We both turned out fine."

"How did they handle discipline?"

"Took away privileges, for the most part," Aidan says. "No corporal punishment. I would never spank a child."

"How about discipline in your family, Molly?" Patti asks, and I think, Oh thank God, because she skipped right over the 'tell me about your family' question.

"Everything was talked to death." I smile. "My father was a therapist, so if I did something wrong, I had to talk it out." There were times I would have preferred a spanking.

"Did your mother work outside the home as well?" Patti asks.

"She was a pharmacist," I say. She might still be a pharmacist, for all I know. Nora would be in her mid to late sixties now.

"Are your parents local, too?" Patti asks.

"No. They died," I say, the first real lie out of my mouth during this interview. I have the feeling it won't be the last.

"Oh, I'm sorry," Patti says. "How about brothers and sisters?"

"No siblings," I say, happy to be able to tell the truth. "And I grew up in North Carolina, so I don't get to see my extended family often." As in, never. The only person I have any contact with is my cousin Dani, and that's minimal. Next to me, I feel Aidan stiffen ever so slightly. He knows we're in dangerous territory. He doesn't know exactly how dangerous.

"Well, let's talk about health for a moment," Patti says. "How old were your parents when they passed away, Molly? And what from?"

I hesitate. "Why does this matter?" I try to keep my voice friendly. "I mean, if we had our own children, no one would ask us—"

"Honey," Aidan interrupts me. "It matters because—"

"Well, it sounds like your parents died fairly young," Patti interrupts, but her voice is gentle. "That doesn't rule you out as a candidate for adoption, but if they had inheritable diseases, that's something the birth parents should know."

I let go of Aidan's hand and flatten my damp palms on my skirt. "My father had Multiple Sclerosis," I say. "And my mother had breast cancer." I wish I'd never told Aidan that particular lie. It might be a problem for us now. "I'm fine, though," I add quickly. "I've been tested for the . . . " I hesitate. What was the name of that gene? If my mother'd actually had breast cancer, the acronym would probably roll off my tongue with ease.

"BRCA," Patti supplies.

"Right." I smile. "I'm fine."

"Neither of us has any chronic problems," Aidan says.

"How do you feel about vaccinations?"

"Bring 'em on," Aidan says, and I nod.

"It's hard for me to understand not protecting your child if you can," I say, happy to be off the questions about my family.

The rest of the interview goes smoothly, at least from my perspective. When Patti finally shuts her notebook, she announces that she'd like to see the rest of the house and our yard. Aidan and I had spent the morning dusting and vacuuming, so we're ready for her. We show her the room that will become the nursery. The walls are a sterile white and the hardwood floors are bare, but there is a beautiful mahogany crib against one wall. Aidan's parents gave it to us when I was pregnant with Sara. The only other furniture in the room is a small white bookshelf that I'd stocked with my favorite children's books. Aidan and I had done nothing else to the room to prepare for our daughter, and I'm glad. I never go in there. It hurts too much to see that crib and remember the joy I felt as I searched for those books. But now with Patti at my side, I dare to feel hope and I can imagine the room painted a soft yellow. I picture a rocker in the corner. A changing table near the window. My arms tingle with an uneasy anticipation.

We walk outside after showing her the bedrooms. We live in a white two-story Spanish-style house in Kensington, one of the older parts of San Diego, and in the bright sunlight our well-maintained neighborhood sparkles. Our yard is small, but it has two orange trees, a lemon tree and a small swing set—another premature gift from Aidan's parents. Exploring our little yard, Patti says the word awesome at least five times. Aidan and I smile at each other. This is going to happen, I think. We are going to be approved as potential adoptive parents. Some birth parents will select us to raise their child. The thought both excites and terrifies me.

Patti waves as she gets into her car in the driveway. Aidan puts his arm around me and we smile as we watch her drive away. "I think we passed with flying colors," Aidan says. He squeezes my shoulder and plants a kiss on my cheek.

"I think we did," I agree. I pull a big gulp of oxygen into my lungs and feel as though I've been holding my breath all afternoon. I turn to him and circle my arms around his neck. "Let's work on our portfolio this weekend, okay?" I ask. We've been afraid to take that step, afraid to pull together the necessary photographs and information about ourselves in case we somehow failed the home study.

"Let's." He kisses me on the lips and one of our neighbors honks his horn as he drives by. We laugh, and Aidan kisses me again.

I remember how I'd wondered if our daughter would have his brown eyes or my blue. His brawny athletic build or my long, slender arms and legs. His easy going nature or my occasional moodiness. Now our child will have none of those things—at least not from us--and I tell myself it doesn't matter. Aidan and I have too much love for just two people. Sometimes I feel as though we're bursting with it. At the same time, I pray I'll be able to extend that love to a baby I didn't carry. Didn't give birth to. What is wrong with me that I have so many doubts?

#

That night, Aidan falls asleep first and I lay next to him, thinking about the interview with Patti. There was nothing there to come back to haunt me, I assure myself. Patti's not going to search for my mother's obituary. We are safe.

The lies I told Aidan when we were first dating—my dead mother and her breast cancer, my cold relatives—had been accepted without question and set aside. He knew I meant it when I said I'd laid the past to rest the day I left North Carolina at eighteen. We never revisited those lies. There'd been no need to, until today. I hope the interview with Patti will be the end of it. I want to move on. We need to create our own healthy, happy, sane and loving family.

I think about our "open communication" Aidan had described to Patti. Our honest relationship. At times I feel guilty for keeping so much about my past from him, but I'm honestly not sure he would want to know. I try to imagine telling him: My mother murdered my father. I'd said those words once and they had cost me. I will never say them out loud again.

Morrison Ridge

Swannanoa, North Carolina

Summer 1990

2

Daddy sat across from me in his wheelchair at the small table in the springhouse, a beam of sunlight resting on his thick dark hair.

"Check it out," he said, nodding toward the window, and I turned to see a dragonfly on the inside of the glass. Centered in one of the wavy panes, it looked as though it had been painted there with a fine-tipped brush.

I got up for a closer look. "A Common Green Darner," I said, although I wasn't certain. "There was one in my bedroom last night, too," I said, sitting down again. "I think it might have been a Dragonhunter."

Daddy looked amused. "You just like the sound of that name," he said.

"True. It was pretty, whatever it was." I'd forgotten a lot of what I'd learned last summer when I was thirteen and so into insects, I thought I'd grow up to be an entomologist. This was the summer nothing felt quite right. One minute I wanted to ride my bike at top speed up and down Morrison Ridge's hilly dirt roads. The next minute I was shaving my legs and tweezing my eyebrows. Even nature seemed confused this summer in the mountains where we lived outside Swannanoa, North Carolina. The laurel was trying to bloom again, even though it was July, and the dragonflies were everywhere. I was careful when I touched the porch railing or the handle of my bicycle, not wanting to squash one of them.

I picked up a chocolate chip cookie from the plate in front of me and held it across the table to him, aiming for his mouth.

"How many calories?" he asked before taking a bite.

"I don't know," I said. "And besides, you're skinny."

"That's because I count calories," he said, chewing the bite he'd taken. "I'm heavy enough for Russell to lift as it is." My father was tall, or at least he'd been tall back when he could stand up, and he had a lanky build that I'd inherited along with his light blue eyes. I doubted he'd ever been overweight.

"So, what are you reading?" he asked once he'd swallowed the last bite of the cookie. I followed his gaze to one of the two twin beds where I'd tossed the book I was currently reading on the thin brown bedspread.

"It's called Flowers in the Attic," I said.

"Ah, yes." He smiled. "V.C. Andrews. The Dollanganger family, right?"

My father always seemed to know something about everything. It could get annoying. "You've read it?" I asked.

"No, but so many of the kids I work with have read it that I feel like I have," he said. "The siblings are trapped in the attic, right? A metaphor for being trapped in adolescence?"

"You really know how to ruin a good story," I said.

"It's a gift." He smiled modestly. "So, are you enjoying the book?"

"I was. Not so sure now that I have to think about the metaphor and all that."

"Sorry, darling."

I hoped he wouldn't call me 'darling' in front of Stacy when she came over later that afternoon. I didn't know Stacy very well, but she was the only one of my friends around for the summer, so when my mother suggested I invite someone to sleep over, I thought of her. She loved the New Kids on the Block and she promised to bring her Teen Beat and Sassy magazines, so we'd have plenty to talk about.

As if reading my mind, Daddy nodded toward one of the three New Kids on the Block posters I'd taped to the fieldstone walls. I'd moved them from my bedroom to the springhouse for the summer. "Play me some of their music," he said.

I stood up and walked over to the cassette player, which was on the floor under the sink. There were not many places to put things in the small cramped springhouse. Step by Step was already loaded in the player. I hit the power switch and music filled the little building. The springhouse had electricity provided by a generator along with a microwave and running water diverted from the nearby spring. Daddy and Uncle Trevor had fixed the place up for me when I was six years old. Daddy must have still been able to walk a bit then, but I could barely remember him without the wheelchair. I'd gone through summers of tea parties in the tiny stone building and I'd spent the night out here a few times with one of my parents sleeping in the second twin bed. Then I spent a couple of recent summers fascinated with the insect and plant life that filled Morrison Ridge's thick green woods. My microscope still sat on the ledge beneath one of the springhouse's two windows, but I hadn't touched it yet this summer and probably wouldn't. Now I was into dancing and music and fantasizing about the boys who made it. Oh, and Johnny Depp. I'd lie awake at night, trying to come up with a way to meet him. In that fantasy I wore contacts instead of glasses and somehow miraculously had great hair instead of my shoulder-length flyaway brown frizz. And I had actual breasts. Right now, I barely filled out the AA cups on my bra. We would fall in love and get married and have a family. I wasn't sure how I was going to make that happen, but it was my favorite thing to think about.

"It's warm in here, don't you think?" Daddy said. He couldn't stand being hot—it made him feel very weak--and he was right about the heat. Despite the fact that we lived in the mountains and the stone walls of the springhouse were twelve inches thick, it was toasty in here today. "Why don't you open the windows?" he said.

"They're stuck."

He looked at the window closest to the sink as though he could open it with his eyes. "Shall I tell you how to unstick them?"

"Okay." I stood up and crossed the small space until I was in front of the window. I stood there bouncing a little in time with the music, waiting for him to tell me what to do. I was always dancing these days, even while I brushed my teeth.

"Now, right where the lower pane meets the upper pane, pound your fist." Daddy didn't lift his hands to demonstrate the way someone else might. Two years ago he might have been able to lift them, at least a little. Now his hands rested uselessly on the arms of his wheelchair. His right hand curled up on itself in a way that I knew irritated him.

"Here?" I pointed to a spot on the window frame.

"That's right. Give it a good whack on both sides."

It took a couple of tries, but the window finally gave way and I raised it. I could hear the rippling sound of the nearby spring, but as soon as I walked to the window on the other side of the springhouse, the sound was overwhelmed by the New Kids singing "Tonight". I used the same technique to open the second window, and a forest-scented breeze slipped across the room.

Daddy smiled as I sat down again. My mother said his smile was 'infectious', and she was right. I smiled back at him.

"Much better," he said. "Even when I was a kid, those windows would stick."

I held his lemonade glass close to his lips and he took a sip through the straw. "I love thinking about how the spring ran though this little house back then," I said. I'd seen old pictures of the building. A gutter filled with spring water ran along one interior wall, and in the old days, my Morrison Ridge ancestors would keep their milk and cheese and other perishable food cool in the water.

"Well, my father changed that early on when he added the windows. Your Uncle Trevor and I helped him, or as much help as we could give him. We were really small. Once it dried out in here, we had sleepovers nearly every weekend in the summer."

"You and Uncle Trevor?"

"And your Aunt Claudia and our friends—with one of our parents, of course--until we got old enough that the boys didn't want to hang out with the girls and vice versa. Later Trevor and I would stay out here alone. There were no beds in here then, but we'd sleep in our sleeping bags. We'd build a fire outside—we had no microwave, of course. No electricity, for that matter." He looked into the distance, seeing something in his memory that I couldn't see. "It was great fun," he said. Then he glanced at the wall above one of the twin beds, to the left of the Johnny Depp posters. "So, what do you keep in the secret rock these days?" he asked. When they were boys, he and Uncle Trevor had chipped one of the stones from the wall to create a small hollow, covering it over with a lightweight plaster cast of a stone. You'd never know the hollow was there unless someone told you. I kept some shells and two small shark teeth in there from the last time we went to the beach, along with a pack of cigarettes my cousin Dani had left on our porch the year before. I didn't know why I was holding onto them. They'd seemed like something exciting to hide at the time. Now they seemed stupid. I also had a blue glass bird my mother had given me for my tenth birthday in the secret rock, along with a corsage—all dried out, now—that Daddy'd given me before my cousin Samantha's wedding. And I kept my amethyst palm stone up there. Daddy had given the stone to me when I was five and afraid to get on the school bus. He'd presented it to me in a velvet-lined jewelry box and I didn't take it out of my pocket for a full year. He told me the story of the stone, how the amethyst had been found on Morrison Ridge land in 1850 when they broke ground for the main house where my grandmother now lived. How it had been carved and smoothed into the palm stone with a gentle indentation for the thumb, then passed down through the generations. How his own father had given it to him, and how it helped him when he was afraid as a child. He'd never believed that the amethyst had actually been found on our land, but he'd treasured the stone anyway and he seemed to believe in its calming powers.

Now he sent away to a new age shop for palm stones—sometimes he called them 'worry stones'--to give the kids he worked with in his private practice.

"The palm stone is there," I said.

"Why up there?" he asked. "You used to carry it around with you."

"Not in years, Daddy," I said. "I don't need it anymore. I still love it, though," I assured him, and I did. "But seriously. What am I afraid of?"

"Not much," he admitted. "You're a pretty brave kid."

"At least I don't have any booze in the secret rock, like you and Uncle Trevor used to hide in there."

He laughed. "I'm glad to hear it," he said. "What time is your friend . . . Stacy Bateman is it? What time is she arriving?"

"Five," I said. He'd given me an idea with his talk of sleepovers. "Could Stacy and I sleep out here tonight?" It would be so cool to stay in the springhouse, away from my parents and Russell.

"Hmm, I don't know," he said. "Awfully far from the house. From any of the houses."

"Yeah, but you just said that you and Uncle—"

"We were older. Besides, now that I remember the sort of things we did out here, I don't think I want you sleeping out here unsupervised." He laughed.

"Like what?" I asked. "What did you do?"

"None of your business." He winked at me.

"Well, we won't do anything terrible," I promised. "Just listen to music and talk."

"You know how spooky it gets out here at night," he said.

"Oh, please let us!"

He looked thoughtful, then nodded. "We'll check with Mom, but she'll probably say it will be all right. Can you help me with a bit of writing before Stacy arrives?"

"Sure," I said, eager to please him now that he'd given me permission to spend the night in the springhouse. And besides, I loved typing and not just because he paid me and I would soon have enough money for the purple Doc Martens I was dying to buy. It was because I felt proud of him when I typed for him. Sometimes I typed his case notes, and I liked seeing the progress his patients made. Daddy would label the notes by number instead of name in case I knew one of his patients, since he sometimes saw kids who went to my school. But most of all, I loved typing his books for him. They were about Pretend Therapy. He had a more technical name for the approach he used with his patients, but that's what he called it when talking to lay people. "In a nutshell," he would say when anyone asked him about it, "if you pretend you're the sort of person you want to be, you will gradually become that person." I saw the approach work with his patients as I typed his notes week to week. So far, he'd written two books about Pretend Therapy, one for other therapists and one for kids. Now he was almost finished with one for adults and I knew he was anxious to be done with it. Soon he'd be going on a book tour set up by a publicist he hired to promote the book for kids, and I'd be going with him, since, he said, I'd been his guinea pig as he developed the techniques he used with children and teens. And of course Russell would go with us. Daddy couldn't go anywhere without his aide, but that was okay. In the three years Russell had lived with us, I'd grown to appreciate him. Maybe even love him like part of the family. He made my father's life bearable.

I stood up and turned off the cassette player. "We should go now if I'm going to type," I said. I only had a couple of hours before Stacy was due to arrive.

"All right," he said. "My walkie talkie's on my belt. Give Russell a shout."

"I can push you home," I said, reaching for the push handles of his chair and turning him around.

"You think you can manage the Hill from Hell?"

"You scared?" I teased him. The main road through Morrison Ridge was a two-mile-long loop. The side of the loop farthest from the springhouse was made up of a series of hairpin turns that eased the descent a bit. But the segment of the road closest to us was a long, mostly gentle slope until it abruptly seemed to drop off the face of the earth. It was the greatest sledding hill ever, but that was about all it was good for. I took the Hill from Hell too fast on my bike one time and ended up with a broken arm.

"Yes, I'm scared," Daddy admitted. "I don't need any broken bones on top of everything else."

"Pretend you're not afraid, Daddy," I teased him again.

"You can be a real twit sometimes, you know that?" he said, but he was laughing quietly. I felt the vibrations in the handles of his chair.

I pushed him down the path that ran from the springhouse to the loop road. The path was nearly hidden, littered with leaves and other debris, but I knew exactly where it ran between the trees. I had to stop a few times to pull vines from the spokes of the wheels, but soon we reached the loop road and I turned left onto it. The dirt road, cradled in a canopy of green, was just wide enough for two cars to carefully pass one another. That was a rare occurrence—two cars passing one another. Only eleven people lived on Morrison Ridge's hundred acres these days, since my two older cousins, Samantha and her brother Cal, had moved to Colorado the year before, much to my grandmother's distress. Nanny thought that anyone born on Morrison Ridge should also die on Morrison Ridge. I tended to agree with her. I couldn't imagine living anyplace else.

Our five homes were well spread out, invisible to one another. The zigzagging roads connected us all. Love did, too, for the most part anyway, because all of us were related in one way or another. But there was also anger. I couldn't deny it. As I walked Daddy past the turnoff to Uncle Trevor and Aunt Toni's house, I felt some of that anger bubble up inside me.

Daddy looked down the lane in the direction of their house, which was well hidden behind the trees. I thought he was thinking about his latest argument with Uncle Trevor who was toying with the idea of developing part of his twenty-five acres of Morrison Ridge. He was trying to talk my father and Aunt Claudia into selling him part of their twenty-five acre parcels so he could go into the development business in a bigger way.

But that wasn't what Daddy was thinking about at all.

"There's Amalia," he said, and I saw Amalia walk around the bend in the lane from Uncle Trevor's house.

I would have recognized Amalia from a mile away. She had the lithe body of a dancer and I envied the graceful way she moved. Even dressed in shorts and a t-shirt, as she was now, she seemed to float more than walk. I set the locks on the wheelchair and ran to meet her on the lane. She was carrying her basket of cleaning supplies and she set it down to wrap me in a hug. Her long wavy brown hair brushed over my bare arms. Her hair always smelled like honeysuckle to me.

"When's my next dance lesson?" I asked as we started walking up the lane toward my father. He was smiling at us. I knew he loved seeing us together. Amalia held the basket in one hand, her other arm warm around my shoulders.

"Wednesday?" she suggested.

"Afternoon?"

"Perfect," she said.

Spending more time with Amalia was one of the highlights of the summer. I felt so free with her. No rules. No chores. She didn't even have certain steps I was supposed to follow during our dance lessons. Amalia was all about total freedom.

We reached my father. "Where's Russell?" Amalia asked.

"Molly's pushing me home," Daddy said.

"Don't lose him on the hill," Amalia warned me, but I knew she wasn't serious. She was not a worrier. At least, she'd never let me see her worry. "Maybe I should help going down the hill?" she suggested.

Daddy shook his head. "Then you'd have an uphill climb all the way home," he said. Amalia lived in the old slave quarters near my grandmother's house at the very peak of Morrison Ridge. The slave quarters had been expanded and modernized, the two tiny buildings connected into one large open expanse of wood and glass. Amalia had turned the remodeled cabin into something pretty and inviting, but there were those at Morrison Ridge who believed the slave quarters was a fitting place for her to live. My father wasn't one of them, however.

"Well, if you're sure you're okay," Amalia said, and I wasn't certain which of us she was talking to.

"We're fine," Daddy said. "It sounds like Molly's enjoying her dance lessons this summer."

"She's a natural." Amalia touched my arm. "Focused and unafraid."

It seemed like such an odd word for her to use to describe my dancing: unafraid. But I loved it. I thought I knew what she meant. When we started moving around her house, I felt like I was a million miles away from everyone and everything.

"Molly has a friend coming to visit tonight," Daddy said. "They're going to stay in the springhouse."

"As long as Mom says it's okay," I added. He seemed to have forgotten that hurdle.

"Yes," he said. "As long as Nora says it's okay."

"An adventure!" Amalia's green eyes lit up and I nodded, but she wasn't looking at me. Her gaze was on my father and I had the disoriented feeling I sometimes got around them. Was it my imagination or could the two of them communicate without words?

Amalia picked up her basket again and put it over her forearm. I spotted a bottle of white vinegar poking out from beneath a dust cloth. Dani told me that after Amalia cleaned their house, it stank of vinegar for days. Amalia cleaned every house on Morrison Ridge. Except ours.

"We'd better get going," Daddy said. "I'd like to get the hill behind us."

"Bye, Amalia," I said.

"See you Wednesday, baby." She waved her free hand in my direction and I unlocked Daddy's chair and began pushing him down the road.

"So what will you and Stacy do in the springhouse tonight?" he asked.

We were passing one of the wooden benches my grandfather had built at the side of the road. I guessed there'd been a view of the mountains from that bench long ago, but now the trees blocked everything. "Listen to music," I said. "Talk."

"And giggle," Daddy said. "I like hearing you giggle with your friends."

"I don't giggle," I said, irked. He still talked to me like I was ten years old sometimes.

"No?" he said. "Could have fooled me."

"Here's the hill," I said. I turned around so we'd be going down backwards and tightened my grip on the handles. I'd seen Russell take him down the hill a dozen times. He made it look simple. "Are you ready?"

"As I'll ever be," he said.

If he'd been capable of bracing himself—tightening his muscles, girding for the ride—I was sure he would have done it, but he could do little except hope for the best.

I started walking backwards, holding tight, digging my tennis shoes into the dirt road. My father and the chair were frighteningly heavy, far heavier than I'd anticipated, and the muscles in my arms trembled. This had been a mistake, I knew as we picked up speed. My heartbeat raced in my ears. When we reached the bottom of the hill, I was close to tears and glad he was facing away from me so he couldn't see my face.

"Ta da!" I said, as if it had been nothing.

"Brava!" he said, then added with a chuckle, "Let's not ever do that again."

"All right," I agreed. Impulsively I leaned forward and wrapped my arms around him. For a moment, I simply held him tight. I didn't ever want to lose him.