Welcome Alex Sokoloff to my Blog!

Please welcome my good friend and fellow writer, Alexandra Sokoloff, to the blog. I use Alex’s wonderful writing tips when structuring my books and I’m grateful to her for sharing them so generously. Welcome, Alex!

Hi everyone! If you’ve been reading Diane’s blog for any amount of time you’ve probably heard about her writers’ group, the Weymouth Seven, that goes off several times a year to have fabulous and productive retreats in great places like the Weymouth Center for the Arts.

Hi everyone! If you’ve been reading Diane’s blog for any amount of time you’ve probably heard about her writers’ group, the Weymouth Seven, that goes off several times a year to have fabulous and productive retreats in great places like the Weymouth Center for the Arts.

Well, I’m one of those writers.

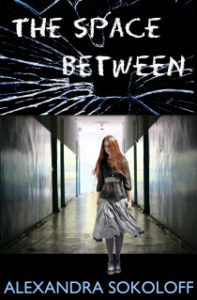

Diane invited me here today because I have two new books out: The Space Between, a spooky YA thriller that I was working on at our last retreat, and Writing Love: Screenwriting Tricks for Authors II, a non-fiction writing workbook that she’s really familiar with, since all of us W 7 tend to use the methods I detail in the book when we’re stuck. I was a screenwriter before I was a novelist, and basically the book is about solving story problems by stealing—I mean borrowing—the tricks the filmmakers who have made our favorite movies use, to help us with our own books.

I think the biggest, most useful trick to steal from film structure is the Three-Act, Eight-Sequence structure.

I think the biggest, most useful trick to steal from film structure is the Three-Act, Eight-Sequence structure.

Most writers and a lot of readers know about the Three-Act Structure:

– Act I (the first 30 minutes of a 2-hour movie or the first 100 pages of a 400-page book) is the SET UP: we learn everything we need to know about the main characters, what their secret hopes and dreams and fears are, and the particular problem that this story is going to be about.

– Act II is usually longer (from 30 minutes to 90 minutes in a 2-hour movie, page 100 to 300 of a 400-page book), because all the meat and action of the story happens here: whatever the main character wants, the antagonist or villain opposes the main character, and the two (or sometimes more!) forces struggle against each other to get what they want, with lots of twists and complications.

– Act III (from 90 minutes in to the end in a 2-hour movie, p. 300 to 400 in a 400-page novel) is where the main character and the villain or forces of opposition come head-to-head in the final battle and resolution.

But movies divide that Three-Act structure further into an Eight-Sequence structure. In almost any two-hour movie, there are eight 15-minute sequences, and if you start looking for sequences, you’ll be amazed at how often movies fall precisely into this format. You can recognize a sequence, a series of scenes, because it all takes place in relatively the same location, or it’s all about the same main action. And the easiest way to see where a sequence begins and ends is to watch for big location changes and big SETPIECE scenes: the cool action or suspense scenes, or thrilling romance or sex scenes, or big comedy scenes, that usually end up in the trailers of movies, like Indiana Jones escaping the booby-trapped cave in Raiders of the Lost Ark, or Clarice Starling bargaining with Hannibal Lecter to save a victim’s life in Silence of the Lambs, or Meg Ryan faking an orgasm in a diner in When Harry Met Sally. Those unforgettable scenes are generally the climaxes of sequences, and while they’re not the only reason we go to the movies, they’re for sure a big reason we love movies.

Well, once an author understands the power of setpieces, s/he can start thinking how to use sequences and setpieces to great advantage in her/his own writing.

After all, novelists have always understood the power of setpieces, even if they didn’t call them that. Think of all the wonderful setpiece scenes and sequences in Gone With the Wind: the burning of Atlanta, Rhett and Scarlett’s scandalous dance at the charity ball, Scarlett’s murder of the Union soldier… the film got all those great setpieces directly from the book.

Rochester taking Jane Eyre up those dark stairs to see his mad wife; the dance scene where Elizabeth Bennet encounters Darcy for the first time; the execution of Sydney Carton in A Tale of Two Cities… novelists have always known how to milk those great scenes for maximum visual impact and suspense – but it’s fun and easy to look at movies for inspiration. One of the things I do in Writing Love is break down ten romantic comedies, sexy thrillers, and romantic adventure and fantasy films in detail to show the structure, setpieces, and other tricks that the filmmakers are using that authors can use in their own love stories.

Another useful trick I talk about in Writing Love is how popular movies and books use the structure and elements of fairy tales. Obviously movies like Arthur (the original) and Pretty Woman and The Princess Diaries are Cinderella stories, and the romantic comedy While You Were Sleeping is an interesting twist on Sleeping Beauty. But a lot of great movies have fairy tale elements without being obvious fairy tales. As grittily realistic as it is, The Godfather is still a retelling of the old tale of the old king who has three sons, one of whom will inherit the kingdom, and it’s the youngest and least likely son who ends up ascending to the throne. Rosemary’s Baby and The Exorcist are stories of changeling children—and you don’t even want to get me started on all the fairy tale elements that made the Harry Potter series and Twilight series such modern classics.

I always use fairy tale elements in my own supernatural thrillers, and my newest, The Space Between, is definitely what I’d consider a fairy tale structure, even though it looks on the surface like a dark, edgy supernatural thriller.

I always use fairy tale elements in my own supernatural thrillers, and my newest, The Space Between, is definitely what I’d consider a fairy tale structure, even though it looks on the surface like a dark, edgy supernatural thriller.

Here’s the story:

Sixteen-year old Anna Sullivan is having terrible dreams of a massacre at her school. Anna’s father is a mentally unstable veteran, her mother vanished when Anna was five, and Anna might just chalk the dreams up to a reflection of her crazy waking life — except that Tyler Marsh, the most popular guy at the school and Anna’s secret crush, is having the exact same dream.

Despite the gulf between them in social status, Anna and Tyler connect, first in the dream and then in reality. As the dreams reveal more, with clues from the school social structure, quantum physics, probability, and Anna’s own past, Anna becomes convinced that they are being shown the future so they can prevent the shooting…

If they can survive the shooter — and the dream.

You could say it’s a very modern and topical story, dealing with the possibility of a school shooting on a high school campus, but it’s also a Cinderella story, with a lonely, alienated girl secretly in love with a boy who is part of the hierarchical royalty of the school, and instead of a prince rescuing a princess, in this story this commoner girl is committed to rescuing the prince. She has prophetic dreams; she finds very strange help in the form of a dwarf who seems to have witchlike powers; and she takes on power of her own. It’s the fairy tale undercurrent that I feel drives the book, and gives it the dreamlike sense I’m always looking for in a spooky thriller.

So I’d love to hear some examples of your favorite setpiece scenes, in books or movies. And what about this fairy tale element? Do you see it working in books and movies that you love?

—————

The Space Between is available in all e-formats, pdf and online viewing: $2.99

Writing Love: Screenwriting Tricks for Authors, II is also available in all e-formats, pdf and online viewing: $2.99

Hi Alex. Thank you for your thought provoking blog. I will need to read it a few times to place my books that I read in a timeline of asssociation but I am already formulating the process:}. Setpiece example in a movie for me would be the scene in The Bridges of Madison County( sorry Diane for coming back to this. On of my favs) is when Robert is driving out of town forever after asking Fransesca to come with him. It is raining and he is sitting in his truck waiting for the lights to turn and she in hers with her husband , just sitting at the crossroads watching the back of his head . She weeps with the rhythm of the wind shield wipers after deciding to sacrifice her happiness to stay with her family.In the time that it takes the lights to change, she places her hand on the door handle and gently but firmly starts to press it down but guilt has her cemented to her seat and she watches Robert drive out of her life forever. Then it’s back to the farmhouse and to the routine of being invisible to her family. Loved it.

Sheree, that’s such a beautiful example it makes me want to see the movie and read the book again! And such a good illustration of how a setpiece doesn’t have to be some special effects extravaganza (although the weather helps!) – it’s so emotionally wrenching and satisfying at the same time.